Despite rapid growth in solar and wind power, hydropower provides more sustainable electricity worldwide than all other forms of renewable energy put together. In 2020, it accounted for one-sixth of global electricity generation. Moreover, only about half of the economically-viable hydro resource has been tapped, a figure which rises to nearly 60% in the developing world, according to a recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

In addition to generating sustainable power on a large scale, hydropower is a major source of system flexibility, owing to the ability to control the flow of water through reservoir turbines and via pumped hydro, the world’s largest and still most affordable form of energy storage. Hydro is thus an excellent complement to variable sources of renewable energy. Hydro dams can also play a key role in irrigation management, flood control and the provision of fresh water supplies.

Damning report

However, large dams, in particular, have generated substantial controversy. Large hydro fell out of favour in 2000, following a report by the World Commission on Dams, which argued that while large dams provide low-cost, renewable energy, they also have significant adverse environmental and social impacts, relating, for example, to the flooding of land to create the reservoirs and the resettlement of communities. Equally, since 2000, the issue of climate change has gained in urgency and along with it the need to generate renewable energy.

The IEA’s report, Hydropower Special Market Report, Analysis and forecast to 2030, underlines the critical role hydropower can play in the energy transition. It provides a warning over the need to reinvest in existing dams to extend their life, and says that, despite the complexities of large dam construction, an expansion of hydropower is critical to meeting climate change goals.

Case by case

An example of the delicate environmental balance played by hydropower was the Aysen project in Chile. This would have seen five large dams built in Chilean Patagonia, adding 2.75 GW of renewable energy capacity to the country’s electricity system of about 25 GW.

Environmental organisations and other opponents argued successfully, first that the impact of the project on the Patagonian wilderness would have outweighed the environmental benefits, and second, that Chile has other more desirable renewable energy options in terms of solar and wind power.

Chile's renewable power generation, 2009-2020, in TWh

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2021A more political and even more controversial project is Ethiopia’s current filling of the giant Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). This has capacity of more than 6 GW and could have a potentially transformative impact on regional electricity supply and Ethiopian economic development.

However, as it is sited on the Blue Nile, it risks disrupting and limiting water supply in the Nile basin, on which Sudan and especially Egypt are heavily dependent. Egypt relies on the Nile for 90% of its freshwater, making GERD’s construction politically fraught.

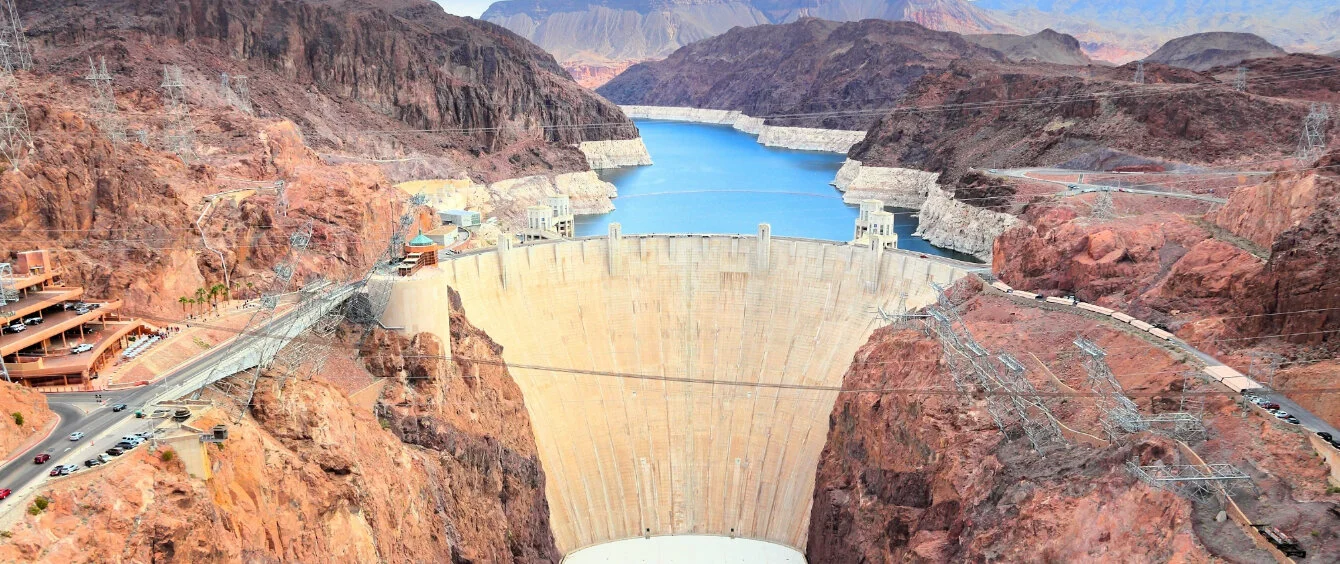

At the same time, large dams can have dramatic positive impacts. The Hoover Dam on the Colorado Rover in the United States was built between 1931 and 1935 and is still providing clean energy today, as well as protecting southern California and Arizona from flooding and providing irrigation water for farming. The dam has been designated a national historic landmark.

Nonetheless, HydroAysen and GERD highlight that large hydro projects need careful assessment on a case-by-case basis, and, as the IEA recommends, strict sustainability criteria need to be applied, and the social and political pros and cons carefully evaluated.

Business case

Hydro dams provide cheap electricity over the course of their long lives, but are difficult to build. They face complex and lengthy permitting procedures because of the associated social and environmental concerns. They also, certainly for big dams, involve large amounts of upfront capital, which in developing countries, in particular, can be problematic, owing to the finances of local utilities and uncertain policy environments.

As a result, most hydro dams historically have been built with public sector involvement. In addition, the IEA estimates that over 90% of hydropower plants since the 1950s have been constructed with some form of long-term contract or power purchase agreement which provides revenue certainty for developers.

Today, the IEA argues, governments must continue to play a supportive role to de-risk hydro projects and allow them to gain popular acceptance.

Yet the energy source remains low down the list of priorities for many, with less than 30 countries targeting hydropower.

Clean energy imperative

The IEA says global hydro capacity is set to increase by only 17%, or 230 GW, between 2021 and 2030, lower than the 23% growth of the preceding decade.

Moreover, by 2030, an estimated $127 billion will be spent on upgrading and maintaining existing dams, primarily in developed economies, but the modernisation of all ageing plants worldwide would require $300 billion. Modernisation provides a major opportunity to upgrade and increase capacity from existing dams, the IEA notes.

Yet global hydro capacity additions could be 40% higher through 2030 with sufficient government support. This would require concessional funding and new business models that share private and public financial risk. The agency also advocates streamlining approval processes to speed up deployment, so long as high sustainability standards are maintained.

The IEA concludes that to meet net zero by 2050, global hydropower capacity needs to expand 45% more than even the accelerated energy transition scenario outlined it its report Net Zero by 2050; A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.