Author: H.-W. Schiffer

In a guest article, Dr. Hans-Wilhelm Schiffer discusses the characteristics of forecasts and scenarios for the energy transition in various studies. In doing so, he critically classifies the approaches pursued by the institutions mentioned. Originally, the article appeared in 2021 under the title “Forecasts and scenarios for global energy supply as the basis for climate policy implications” in the magazine VGB PowerTech. This is the third part of the series of articles.

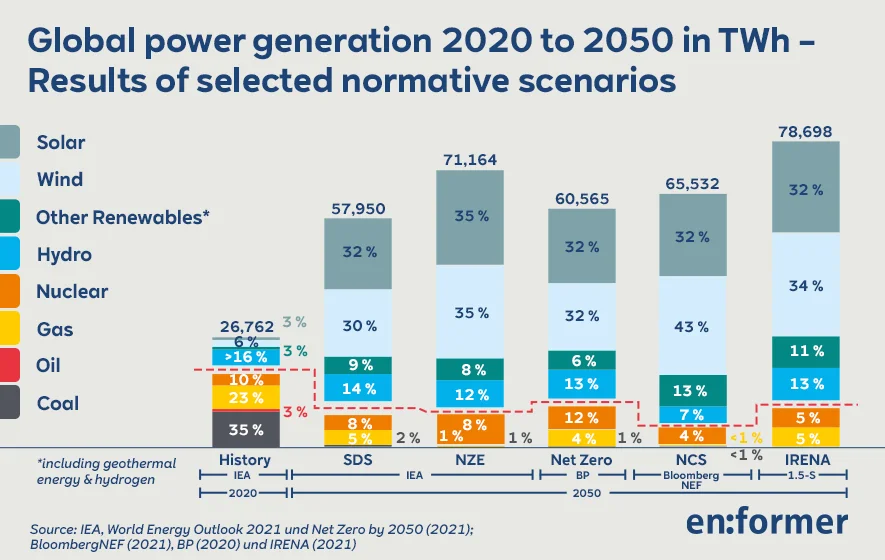

Increased electrification will play a key role in meeting the goal of limiting global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius. A comparison of several normative scenarios that follow this requirement shows that institutions such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) or the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) as well as, for example, the companies BP and BloombergNEF assume that global electricity generation must double or even triple by 2050 compared to the level in 2020.

Professor Dr. Hans-Wilhelm Schiffer

Lecturer at RWTH Aachen University, Member of the Studies Committee, World Energy Council, London and Chairman of the Energy for Germany editorial group at the Weltenergierat – Deutschland, Berlin

A drastic change in the energy mix is also displayed. The share of renewable energies in global electricity generation will increase from 28 percent in 2020 to – depending on the scenario – in a range of 83 to 95 percent in 2050. Electricity generation from hydropower, currently still by far the most important renewable energy source, will continue to increase in the future, as will electricity generation from biomass and geothermal energy.

However, these renewable energies cannot keep up with the particularly dynamic growth of wind power and solar energy. Wind and solar alone account for around two thirds of electricity generation in the normative scenarios of the institutions mentioned in 2050.

As a reference, just 9 percent of global electricity generation was sourced from wind power and solar energy in 2020. In addition to renewable energies, nuclear energy and natural gas are also assigned a significant role in global electricity supply. In contrast, the proportion of coal in the normative scenarios falls from the current 35 percent to 2 percent and less by 2050.

The key role of hydrogen

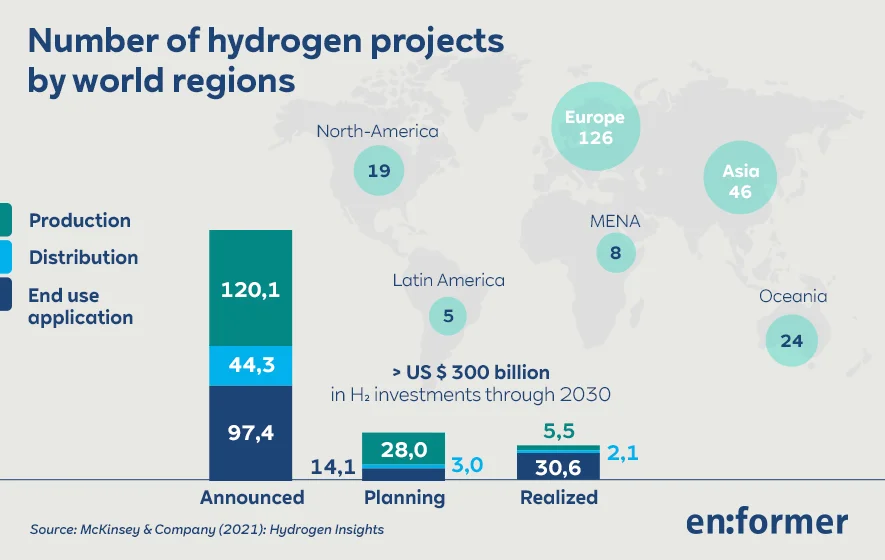

Alongside a strong growth in electricity demand, hydrogen plays a key role in the desired transformation of energy supply. More than 50 countries – including Germany – have enacted or planned hydrogen strategies. In a study presented in 2021, McKinsey identified hydrogen projects worldwide, a large proportion of which are in Europe.

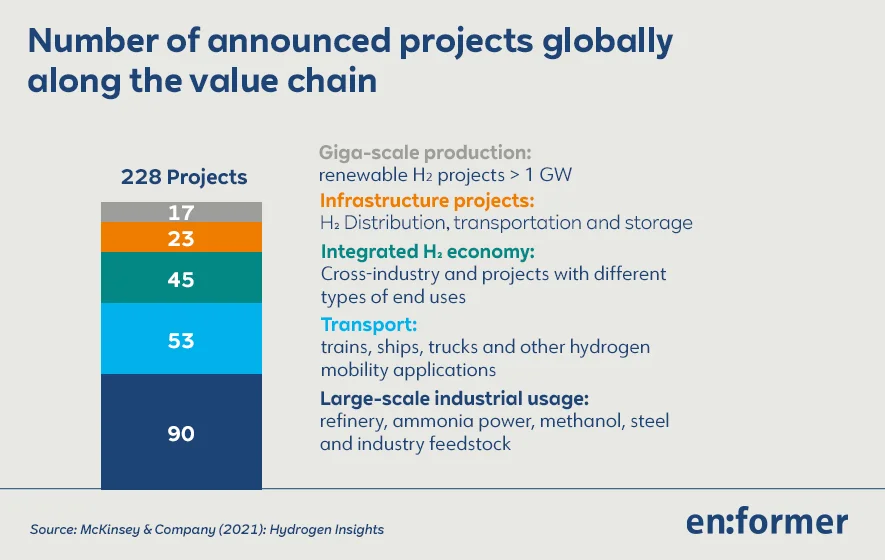

In addition to strong growth in electricity demand, hydrogen plays a key role in the envisaged transformation of the energy supply. More than 50 countries – including Germany – have enacted or planned hydrogen strategies. In a study presented in 2021, McKinsey identified 228 hydrogen projects worldwide, the majority of which are in Europe. But other regions of the world also rely heavily on hydrogen. The project list is large across the globe, especially in Asia, North and South America, Australia, Africa and the Middle East.

If all planned and announced projects are implemented, an investment amount for hydrogen of around US $ 300 billion would be mobilized by 2030. Of this investment sum, more than US $ 80 billion is covered by projects that are already being implemented or are at a specific planning stage. The development of a global market for hydrogen offers great opportunities for international cooperation, trade relationships and the establishment of new value chains.

In Europe, the hydrogen that will be required there in the future can only be generated to a small extent, as sufficient potential that can be used cost-effectively is not available. This also applies in a comparable way to countries like Japan or Korea. Increased international cooperation is therefore of paramount importance. Accordingly, bilateral and trilateral partnerships have already been concluded or are in prospect.

Hydrogen Projects in Europe

One example in this context is the Hydrogen Energy Supply Chain (HESC) pilot project, in which hydrogen is to be produced in the Australian state of Victoria and transported to Japan by ship. The hydrogen will be obtained from lignite. It is planned to capture the resulting CO2 emissions and store them under the sea floor using CCS technology in order to produce blue hydrogen.

Another intergovernmental project is HySupply. The aim of the German- Australian cooperation, which was founded in 2020 and will run for two years, is to identify and analyze possible business models for the supply of green hydrogen between the two industrialized countries.

At the regional level, the Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI) Hydrogen was launched in December 2020, with which the market ramp-up for H2 technologies within the EU is to be supported along the entire value and use chain.

22 EU member states as well Norway signed the Manifesto for the development of a European “Hydrogen Technologies and Systems” value chain. This confirms that the countries wish to promote joint hydrogen projects across Europe. Over 400 projects from 18 countries have now been registered within the EU. The start for the implementation phase was on May 28, 2021.

The 228 projects announced worldwide span the entire value chain – from production to infrastructure, transport and use of hydrogen. It is expected that in the longer term most of the hydrogen will be generated by electrolysis using electricity from renewable energies.

In addition, electricity from nuclear power plants opens up the possibility for CO2-free production of hydrogen. Low-CO2 generation is also possible on the basis of natural gas and coal, provided that the CO2 is captured in the production process and used or stored. Projects for the use of hydrogen are aimed in particular at the transport sector and industry and there on areas that are difficult to electrify. Furthermore, hydrogen will play an important role as a storage medium in the future.

Results of the Glasgow International Climate Conference

At the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was held in Glasgow from October 31 to November 13, 2021, the Glasgow Climate Pact was unanimously adopted. The essential elements of this agreement include:

- The long-term goal of keeping the global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius and continuing efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels was confirmed.

- Global CO2 emissions are to be reduced by 45 percent by 2030 compared to 2010 levels and reduced to net zero by the middle of the century. Furthermore, drastic reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions are to be made.

- Increased efforts must be made to reduce the generation of electricity from coal (as far as this takes place without the capture, use or storage of CO2) (literally it means: “phase down of unabated coal power”) and to eliminate inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels (“Phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”).

- The industrialized nations are making at least US $ 100 billion a year available through 2025 to support developing countries in efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions and in efforts to adapt to climate change.

- The importance of increased international cooperation in innovative climate protection measures is emphasized.

In the aftermath of COP 26, the International Energy Agency stated that in view of the more stringent climate protection obligations (updated pledges) presented by a number of countries at the conference, it can be assumed that the global temperature rise can be limited to 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2050. However, this presupposes the full implementation of the commitments made.

At the same time, it becomes clear how ambitious the goal set for 2030 is when you examine it more closely. To date, China has only committed itself that the country’s greenhouse gas emissions will not increase after 2030 and that greenhouse gas neutrality should be achieved by 2060. If, however, China’s emissions, which in 2020 amounted to just under 12 billion tons of CO2 and thus corresponded to a good third of the global emissions burden, do not peak until 2030, the “rest of the world” in 2030 could at most emit up to 5 billion tons of CO2. That would correspond to a reduction of around three quarters within the next nine years.

Conclusion

The future of energy supply looks very different from the past. This is shown by the projections and scenarios that have been presented by international organizations and global corporations in recent months. A change is taking place from an age marked by fossil fuels to an energy world where renewable energies dominate.

The decisive keys for achieving the ambitious climate targets are the accelerated improvement of energy efficiency, the broad implementation of the technology of capture and use or storage of CO2, the massive expansion of renewable energies to cover the rapidly growing demand for electricity and the reliance on hydrogen in the sectors that are difficult to electrify. The pricing of CO2, if possible implemented at a comparable level worldwide, technology-neutral funding mechanisms by governments and increased international cooperation are seen as crucial in order to achieve the sustainability goals. Above all, this includes the goal of limiting global temperature increases to well below 2 degrees Celsius.